Evaluating New Zealand’s earthquake-prone building system

Why focus on earthquake-prone buildings?

New Zealand’s seismic risk is no secret. From the devastating Canterbury earthquakes in 2010–11 to Kaikōura in 2016, the risks from the impacts of earthquakes on some of our building stock have been exposed. That’s why, in 2017, major changes were made to the Building Act 2004 to strengthen how earthquake-prone buildings (EPBs) are identified, assessed, and remediated.

Now, nearly a decade later, MBIE commissioned a review to ask: is the system working as intended?

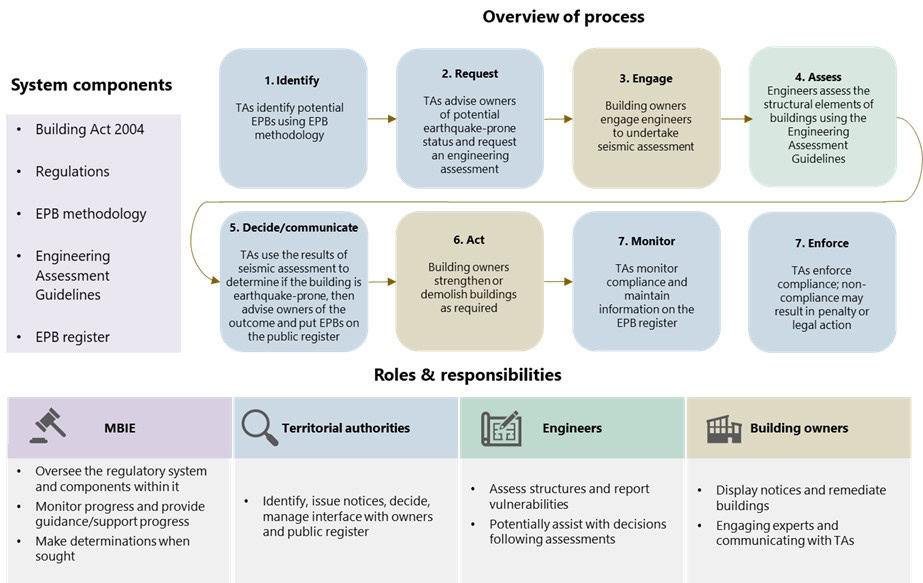

An overview of the EPB system post-2017 is shown in Figure 1 below, including the process to remediate an EPB and the respective roles and responsibilities of MBIE, territorial authorities (TAs), engineers, and building owners at each stage of the process.

Last week, Building and Construction Minister Hon Chris Penk announced the outcome of a wider review of the EPB system in a shift to what he has referred to as a “fairer, risk-based system that will bring enormous relief by lowering costs for building owners, while keeping Kiwis safe.”

Figure 1: Overview of system components, process, roles and responsibilities

A system under review

As part of the wider review, we were asked to examine how MBIE, TAs, and engineers had been fulfilling their roles, and to assess which elements of the current EPB system were working well and which were not.

Our review found that MBIE, TAs, and engineers were largely carrying out their responsibilities as intended. Compared with the pre-2017 period, there was greater national consistency. Most TAs in high-risk zones had identified EPBs, and over 80 per cent of buildings on the EPB register had undergone engineering assessments. As at January 2025, a total of 6,717 unique buildings had been listed on the national EPB register since 2017. Around a quarter of these buildings -approximately 1,714 – were no longer considered earthquake-prone, with 945 having been strengthened, 258 demolished, and 361 reassessed as not earthquake-prone.

However, the scale of the challenge remained significant. With most statutory remediation deadlines still several years away, many owners appeared to be waiting until the last possible moment to take action. This created risks of bottlenecks and inconsistent compliance.

Figure 2: Overview of our findings

JC-SAR is the Joint Committee for Seismic Assessment and Retrofit of Existing Buildings

MBIE could strengthen its role as steward

MBIE is the system steward – it sets the rules, maintains the register, and issues guidance. Our review found that MBIE had delivered the core components of the system: the EPB methodology, engineering guidelines, public register, and training roadshows. These had contributed to greater consistency nationwide.

However, we found that MBIE’s oversight could be strengthened. Communication channels were sometimes unclear, and the register itself was not always user-friendly for TAs. As part of its stewardship role, we suggested that MBIE could provide stronger oversight and establish more effective feedback loops to improve understanding of practices and emerging issues. Importantly, there should be clear mechanisms for making improvements and supporting learning across the system.

Questions were also raised about whether the EPB requirements appropriately reflected the risks and their wider impacts. These issues were a central focus of the wider review, and the recently announced system changes are intended to address them.

“The system had made real progress in reducing seismic risk. However, with more than 6,500 buildings having appeared on the EPB register (and still over 5,000 remaining), and many remediation deadlines still years away, the real test appears yet to come…”

Sapere

Territorial authorities on the front line

TAs are responsible for identifying EPBs, issuing notices, and ensuring compliance. As at early 2025, 55 of New Zealand’s 67 councils had buildings listed on the EPB register, including almost all those located in high seismic risk zones. Around 83 per cent of the buildings listed on the register had already received engineering assessments.

Some councils had gone further by offering case management and targeted financial or technical support to building owners. These approaches appeared to have delivered better outcomes.

However, challenges remained. Smaller or lower-risk TAs sometimes faced resourcing constraints, and interpretation of the rules continued to vary. Enforcement was also difficult – while compliance tools were available, in practice many owners delayed taking action until the final possible moment. This created a risk of a last-minute surge in demand for engineers and builders as statutory deadlines approached.

Engineering assessments: progress and inconsistency

Engineers provide the assessments that determine whether a building is rated as earthquake-prone. The review found that assessment quality has improved, particularly through the use of peer review processes and engineering panels. However, some inconsistency remained, with variation in how engineers applied professional judgement when determining seismic ratings.

Different engineers sometimes reached differing conclusions for similar buildings, reflecting both variations in professional judgement and practice, as well as differences between the approaches used for EPB assessments and the focus of undergraduate training. There were calls for more case studies, refresher training, and clearer guidance on applying the Engineering Assessment Guidelines.

The critical role of building owners

While building owners were outside the scope of this review, their role was critical. Many owners displayed notices as required, but remediation often lagged until deadlines loomed. Financial constraints, complex ownership structures, and limited access to engineering expertise all played a part.

System-wide challenges

Several cross-cutting issues stood out:

- Understanding %NBS: The percentage of new building standard (%NBS) was often misunderstood, and it was widely felt that the terminology was misleading. Tenants frequently assumed that a low %NBS indicated immediate danger, even when the actual risk to life was small. This misunderstanding drove vacancy decisions and influenced rental markets in ways not intended by policymakers.

- Resource pressures: Suitable engineers were in short supply, particularly outside the main centres. If too many owners waited until the last minute to act, bottlenecks appeared inevitable.

- Economics of remediation: Some buildings were unlikely to be remediated because doing so was financially unviable. There was often a significant step change in the cost of remediation relative to increasing a building’s seismic rating, which was not always justified by the level of risk. In many cases, the cost could not be recovered through returns on investment or the underlying value of the building.

- Conservatism across stakeholders: MBIE, TAs, and engineers all tended to err on the side of caution, for a range of reasons including interpretation of the EPB methodology and engineering guidelines, levels of experience with the EPB system, and liability concerns. Collectively, this reduced efficiency and led to several unintended consequences.

What was working well

- Greater national consistency compared with the pre-2017 system.

- More than 1,700 buildings removed from the EPB register to date.

- Strong collaboration across engineering societies and panels to test and align professional judgement.

- Targeted TA-led initiatives – such as financial support and case management – that proved effective.

- Strengthening efforts concentrated in high-risk regions, with Wellington and Canterbury leading progress.

Areas for improvement

- Clearer guidance and enhanced training for both TAs and engineers.

- Strengthened MBIE oversight, supported by improved monitoring and feedback mechanisms.

- More accessible and user-friendly tools, particularly the EPB register.

- A stronger focus on risk-based prioritisation to ensure limited resources are directed towards the highest-risk buildings first.

- Greater support for building owners facing complex barriers to remediation, especially financial and governance challenges.

What this means for New Zealanders

Earthquake safety isn’t just about engineering – it’s about people, communities, and the buildings we live and work in every day. The system had made real progress in reducing seismic risk. However, with more than 6,500 buildings having appeared on the EPB register (and still over 5,000 remaining), and many remediation deadlines still years away, the real test appears yet to come. The recent changes are intended to focus effort on the areas of highest risk and to help manage the pressures that were expected to emerge as deadlines approached.

The bottom line

The EPB system was stronger and more consistent than before 2017. MBIE, TAs, and engineers were largely fulfilling their roles, but challenges around resourcing, timing, and communication remained. Without the renewed focus announced this week by the Government, there was a risk that progress would have stalled, the most challenging cases might have gone unaddressed, and building owners could have faced financial burdens that were not justified by the level of risk.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the input from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, the Seismic Review Steering Group, and the Joint Committee for Seismic Assessment and Retrofit of Existing Buildings, as well as the external experts we consulted at Holmes and ResOrgs, and the stakeholders who provided their time and thoughts during interviews or in completing our online survey, as well as the Parliamentary Counsel Office for providing information to us.

Our team included

- David Moore

- Angus White

- Hamish Hann

- Jamie O’Hare

- Douglas Yee

A final reflection

At Sapere, our research helps guide government policy and provides evidence to inform decisions that affect communities across New Zealand. Reviews such as this one are critical in shaping how we prepare for and respond to seismic risk. By bringing clarity to complex systems, our work contributes to safer, more resilient cities and towns – ensuring that policy choices today have a positive impact on the country’s future.